Trials and Triumphs

Starting a Family Tradition

One Family’s Story of the Trials and Triumphs

By: Susan Bowman

www.LadyFather.com.

Family is the most vital human connection there is. We all have this connection somewhere in our history and many of us are fortunate to have a living family which brings us many occasions for this special human connection. Unfortunately, many families in this busy society, don’t take advantage of these opportunities and they are missing moments of real joy, moments that make lasting and precious memories.

Keeping in contact with family is simple, when we make the effort. It used to take a lot of effort to keep in touch before the computer age; now it is simpler, quicker, and many times, more effective. While we used to be limited to phone calls and letters, we now have email, text messages, document/photo sharing sites, mobile phones, Skype and Oovoo just to name a few of the electronic marvels available to many people.

The McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Tx is a very popular destination, as is The River Walk, for reunion activities due to the variety of activities and beauty.

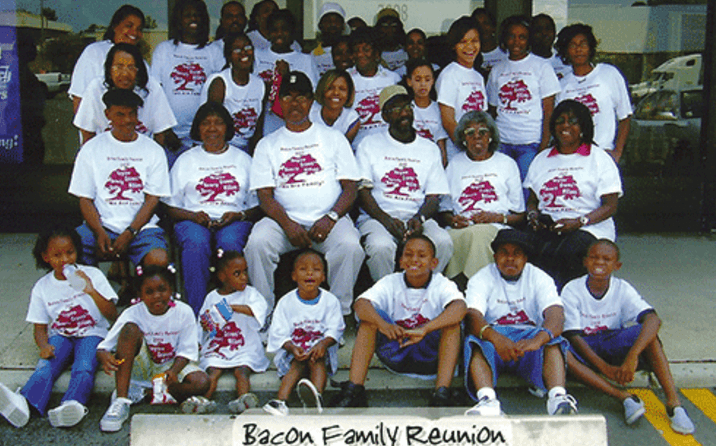

The best and the most enjoyable way to keep in touch with family is by spending time with as many members of the family as possible. If your family is spread around the country or even the world, this can be a real challenge; that is why my family has adopted the “Annual Family Reunion.” Usually, when thinking of a family reunion, you might think about a get-together once every 20 years or so. These are grand occasions and should definitely be part of the family plans. But, to really keep in touch and to be able to enjoy watching the children grow up and the adults grow older, there is nothing better than drawing together as many family members as possible every year.

As a “family reunion-er” of more than 30 years, I can attest to their value, not to mention all the fun there is to be had. We started over 30 years ago when my parents built a house on a lake in southeastern Virginia and thought it would be nice to invite family to spend their summer vacations on a lake for free. So they did and families streamed into Virginia on a weekend in early August, filling up my parents’ small house and the weekend homes of their neighbors. Some brought campers and by the time they all arrived and got settled in the various venues, we had our first feast together, caught up with each other until the wee hours of the morning, we were all exhausted and went off to our assigned places for a good night’s sleep.

These reunions were great fun, but after the first few years, it became clear that my parents could not bear the cost of everyone’s vacations, and the “share-the-costs-method” was born. Everyone who made purchases for food, beverages, gas for the boat, anything that everyone shared, put their receipts in a basket and at the end of the week, they were totaled up and everyone was presented with a bill for their share. It sounds crass and business-like but, it is by far and away the best way to deal with the group’s expenses. We did learn to make certain allowances for folks who had special diets and couldn’t eat or drink most of what had been purchased; they were charged less using a smaller percentage. Also, there were people who didn’t drink alcoholic beverages, so everyone who purchased any pooled their receipts among themselves and shared the expense.

As we prepared for the 3rd reunion, my father declared that he wasn’t interested in having them anymore if my mother continued to get stuck with all the work. It seemed that many people assumed that since it was her house and they didn’t know where things belonged, that she would prefer to load, run, and empty the dishwasher – something that had to be done at least three times a day. It was always falling to her and a few others to run the vacuum and keep the rooms straight and neat; my Dad said that unless people started pulling their weight, he was shutting the reunions down.

So we sat down and devised a way to share the work load and “The Schedule” was born. Everyone was assigned a chore/task – setting the tables, cooking, busing the tables, dishwasher duty, trash pick-up and disposal, ice replenishment (this was vital!), and what we called “House Police.” This entailed picking up the kids’ toys (although most parents were pretty diligent about making sure their kids picked up their own), straightening up the living room and deck, emptying ashtrays (in the early days, many people smoked and it became a huge issue in years to come), and vacuuming. This had to be done at night before retiring so the house would be livable for the next day.

We presented “The Schedule” to everyone at a “Family Meeting” soon after arrival and explained the reason we developed it (although no one ever knew how close Dad came to stopping the whole show!), going over the tasks and how we assigned everyone, and then waited for the explosion. It came but not like we thought – everyone loved it! They were unaware how much work it took to have 20-30 people in one place for a week and they were all appalled to discover how much of that work had been left for so few people. Everyone promised solemnly to abide by “The Schedule,” which was printed on a large piece of cardboard and attached to the side of the refrigerator. With only a few forgetful moments, it worked like a charm.

Over the next few years, we learned who was good at what and who needed prodding to do certain chores. We began to add the youngest children in, pairing them with an older child or adult to teach them the “reunion ways” from the cradle! We also discovered an amazing opportunity to bring certain members of the family together who rarely got to see each other; we paired those folks together for chores, especially cooking. As the years went by, many a strained or distant relationship was healed and/or strengthened over hours in the hot kitchen cooking dinner for the whole family. We shared recipes and new ideas; we renewed relationships and we made many new traditions.

Favorite dishes became staple items on the week’s menu, those who had access to regional culinary delights (like Georgia peaches and South Carolina pecans and cantaloupes) came every year bearing their assigned foods, and some, like Cousin Bob became the cook to avoid cleaning up after when he began bringing frozen seafood for a Tempura feast. His ability to completely coat the kitchen with grease became legendary, making him the hero of the week with his fabulous feast but also the cook to avoid.

Our family reunions were yearly for a long time, but in recent years, the “middler” families (these are kids my son’s age and their kids) have had their activity level increased as their children get more and more involved in school, sports, and other community activities that continue into the summer or start up early in August. This depleted us several times and kept one or two away, it seemed, almost every year in the past 5-10 years.

We got it back together this year and decided that we love it but that we would begin opting for every 2 years instead of every year. Through it all, we discovered the importance of coming together – whether for a day, a few days, a week, or whatever amount of time enough people could spare. Some planned their entire week’s vacation to fall on reunion week and some found they could only breeze in and out for a few days. It didn’t matter, in fact it made it more fun when people would be arriving off and on all week. We all got to stop what we were doing drag out of the water or off the deck and greet the new arrivals or, toward the end of the week to say a tearful good-bye until next year. Of course, no family is perfect and we discovered that the foibles and faults of our relatives become more pronounced after a week in the same crowded house. We also discovered how to live with each other’s faults and shortcomings and that, no matter how pronounced they became, we loved each other anyway. We learned to overlook things of little importance and to soak in the important stuff – the pains of life, the joys of children and grandchildren, the gifts we knew nothing about, and the great little moments of insight into our heritage and our life as a family. These are the things we now cherish and what makes family reunions the absolute best way to keep in touch with each other.