The Red Ball Express

Fighting Nazis and Racism During WWII

Fighting for respect at home and abroad.

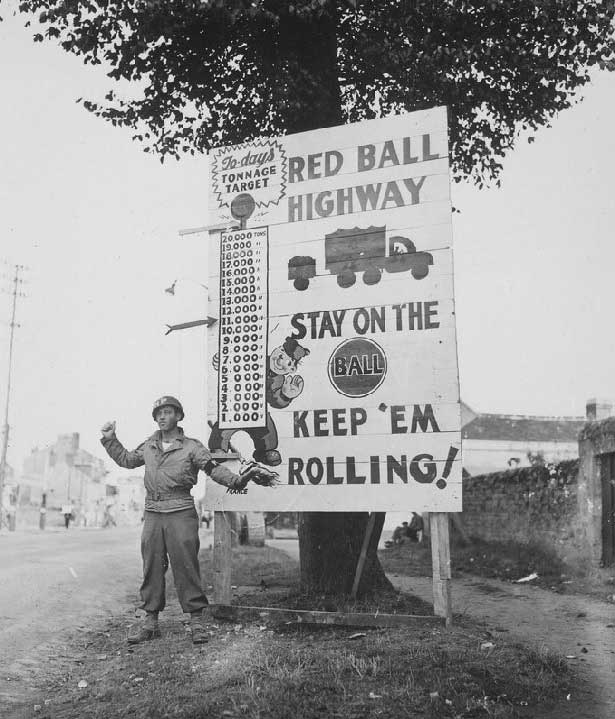

Photo from National Archives

It is often said that a picture is worth a thousand words. Great photography can transport the viewer to a place and time, and evoke emotions where words often pale. Much of what we know today about World War II comes from the images that thousands of combat photographers took to document the human triumphs and tragedies wrought by war. Think of the iconic Iwo Jima flag-raising photo, or the image of allies liberating emaciated survivors at Buchenwald to understand the power of photography to tell a story.

Sometimes, though, words might just be worth a thousand pictures. Because hidden in the millions of photographs taken during WWII, is a photo that is easily bypassed—a grainy shot of a group of men standing at ease, next to a convoy of trucks that reaches into the distance as far as the eye can see. At first glance, nothing striking, but a closer inspection of the photo shows that every face that is visible belongs to a Black man. And there are hundreds more of these everyday shots—Black men fixing engines, Black men driving trucks, and Black men loading equipment for transport. Not iconic photos in any way, but photos that beg for the rest of the story to be told.

And that story really begins with D-Day—when the largest invasion force in history began landing on the beaches of Normandy, France on June 6, 1944. Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower knew the operation would be a race against time, and that the German’s counterattack would be the deciding factor in success or failure of not only the invasion, but perhaps the war. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, nicknamed “Desert Fox” for his cunning leadership in North Africa, was commanding the German army in France, and would move his best units, including Panzer (tank) divisions, quickly into position once he knew where the Allies would land. Something had to be done to give the Allies an edge. So, Eisenhower made an unpopular decision, ordering the bombing of the French railway system. This, he believed, was the best way to hamper the Germans’ ability to quickly bring in troops and heavy equipment to the beachhead for a counterattack.

The tactic worked exactly as planned, and the extreme bravery and perseverance of the Allied forces put the German Army into full retreat eastward across France by August of 1944. But the bombing of the rail system was a double-edged sword. It had succeeded spectacularly in keeping Rommel’s supplies and reinforcements at bay, but it also created a serious logistics problem for the Allies, who now had over 1 million soldiers ashore. The US Third Army under General George S. Patton Jr. was covering more than 80 miles a week as it worked to liberate France from the Nazis, and as Eisenhower noted, “with 36 divisions in action, we were faced with the problem of delivering from beaches and ports to the front lines some 20,000 tons of supplies every day.” With rail transport out as an option, and most of the ports in France damaged or still under German control, the army would need a plan, and they needed it quickly.

Keep them rolling.

The only way to deliver the vital supplies needed would be the way Eisenhower had forced the Germans to do it—slowly, by truck, over bombed-out, narrow roads that weren’t designed to handle heavy equipment and military vehicles. Two officers, Lt. Col. Loren A. Ayers and Major Gordon K. Gravelle, spent 36 hours brainstorming and devised a creative solution that would capitalize on the abundance of trucks the Americans had unloaded in Normandy. The temporary solution would be a convoy system, named “The Red Ball Express,” a massive fleet of some 6,000, “deuce-and-a-half” ton GMC “Jimmy” trucks, along with other vehicles, running continually in a loop, jam-packed with supplies heading to the front, then returning empty. (The “Red Ball” name came from a railway practice of marking priority cars with a big red dot, and these Red Ball Express trucks would be emblazoned with the same red dot and given priority on the roads.) So the Allies had a plan—but there was a problem—finding enough drivers to move the staggering amount of supplies needed. Colonel Ayers was tasked with finding 23,000 drivers—two for every truck, so one could sleep while the other drove.

And it’s here that the story of those pictures comes to life. Upon entering the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the United States was fighting a war for freedom abroad, while at home, it remained divided along racial lines by Jim Crow laws. Those entering through the “Blacks Only” door saw little equality in the “separate but equal” daily life to which they were relegated—Blacks struggled to get hired for high-paying jobs, their children were forced to attend underfunded schools, and they endured targeted violence, often at the hands of those hired to “protect and serve” the community. But even while being denied basic human rights at home, Black men and women didn’t hesitate to heed the call to serve their country when the need arose.

During WWII, racism didn’t keep Blacks from going overseas with the armed forces, but it certainly influenced the work they were assigned to do once there. The critical need for manpower forced the Army to field several African American combat units during the war, but the overwhelming majority of the 900,000 Blacks that served in the Army during the war were limited to support jobs. Black soldiers were routinely assigned to labor and service units and given jobs in the mess hall, the laundry, in construction and the motor pool rather than combat and leadership roles. So it was to this underutilized pool of men that Colonel Ayers looked. And it was these Black men who would make up 75 percent of the drivers who would meet the Allies’ logistics challenge and create the military legend that was the Red Ball Express.

Most of the Black men Colonel Ayers found were under the age of 24, and few had experience driving trucks before the war. Driving day and night, over a 700-mile supply route, the Red Ball truckers earned a reputation as tireless and fearless. With little training, the two-man teams made the 54-hour round trip in the rough-riding trucks, over roads that went from deeply rutted to slick cobblestone and wound through little towns with such tight corners that there was no room for even the slightest navigation error. And half of this journey was done in pitch dark. The drivers slept little and drove fast—some mechanics even removed the governors to allow an increase in top speed—because they knew how high the stakes were for the units they had to keep fed, armed, and rolling. Guards were posted at every intersection along the route to guarantee the trucks did not have to stop for anything, but the drivers still faced Luftwaffe strafing attacks and German snipers along the route. Everywhere the drivers saw the sights of war—bombed out hamlets, abandoned German tanks, injured soldiers, and hastily dug graves.

In a message to the Red Ball Express in October of 1944, Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote, “To it falls the tremendous task of getting vital supplies from ports and depots to combat troops, when and where such supplies are needed, material without which armies might fail. To you drivers and mechanics and your officers, who keep the Red Ball vehicles constantly moving, I wish to express my deep appreciation. You are doing an excellent job.”

After many railway links were repaired and the port of Antwerp opened, the drivers of the Red Ball Express returned to their respective units. In its 82 days of operation, the convoy had made the American military the most mobile force in the war, and was hailed as having played an essential role in the Allied victory in Northern Europe. Upon forming the Red Ball Express, General Plank had declared, “Let it never be said that [a lack of supplies] stopped Patton when the Germans couldn’t.” And it didn’t—because of the devotion to duty of thousands of Black men who had been denied their full rights as American citizen, but who were committed to doing their part to win the war.

I authored a book on the Red Ball Express entitled “Red Ball Express: Greatness Under Fire”. It was released in 2020.

I so loved this fact about my black brothers in arms driving the duce and a half ( 2.5 ton). During my service in the Army, I was a 92 Y (Supply) My primary vehicle was a duce and a half, in fact that is how I learned how to drive a “stick” I served 1988-1997 active duty and 1984-1987 Army Reserves!