Shirley Chisholm Paved the Way for Today’s Black Women Leaders

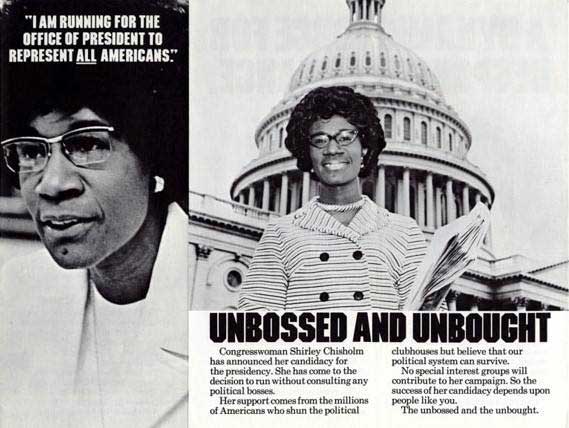

“Unbought and Unbossed”

“If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”

– Shirley Chisholm

Black History Month got a fitting kickoff this February when voter suppression activist and politician Stacey Abrams was announced as a nominee for the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize. This comes on the heels of Kamala Harris’ vice-presidential win and a record 26 Black women taking congressional seats. After years of being shut out of politics, Black women are now transforming it. But long before Stacey Abrams or Kamala Harris were influencing America’s political agenda, the very door these leaders would later walk through was being kicked down by an underappreciated but pivotal Black woman — Shirley Chisholm.

Chisholm made a career out of challenging the idea that only White men deserved a seat at the political table. In 1968, Chisholm made history as the first Black woman to serve in the United States Congress. Four years later, the feisty politician nicknamed “Fighting Shirley” again rocked the status quo by becoming the first Black woman from a major party to campaign for the country’s highest office—President of the United States.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1924, Chisholm learned about the value of hard work and the plight of the poor watching her immigrant parents struggle to provide for their four children during the Great Depression. To make ends meet, her father, a factory worker from Guyana, and her mother, a seamstress from Barbados, made the difficult decision to send Chisholm and her sisters to live on their maternal grandmother’s farm in Barbados. Chisholm credited the excellent education she received there, along with the loving support from her grandmother, as critical to her future success.

After returning to the states, Chisholm attended high school in Brooklyn. She was an excellent student, and upon graduating, was awarded tuition scholarships to several prestigious universities. Because she was unable to afford the room and board, the ever-practical Chisholm decided to live at home and attend Brooklyn College. She was a standout there, both for her activism with campus organizations, and for her debating prowess. It was during this time that Chisholm saw firsthand how Black women were barred from certain campus social clubs and leadership roles. Looking back, Chisholm told an interviewer, “In college, I became angry.” After graduating cum laude in 1946, Chisholm would harness her anger to challenge an entire system.

National Archive: Clip from Accomplished Women: Shirley Chisholm (NAID 54173)

The newly-graduated teacher began her career at a daycare center, but as the saying goes, “the cream rises to the top,” and it wasn’t long before she was tapped to direct the entire operation. After she received a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1952, Chisholm was recruited to work as an educational consultant for New York City from 1959 to 1964. Working for the city gave her an inside look at local government, and at how few women were represented there. She began volunteering with organizations that advocated for the rights of the poor and the disenfranchised—the League of Women Voters and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People among them. She also became active in the Democratic Party, and in 1964, the woman who described herself as “literally and figuratively a dark horse,” was elected to the New York state legislature in a landslide victory; becoming only the second African-American woman to serve in Albany.

When a court-ordered redistricting created a windfall—over 80 percent of the registered voters in her reformed neighborhood district were Democrats—Chisholm saw her chance to make a bigger mark on the national stage. After defeating Black civil rights activist James Farmer for the seat, she became the first African American woman in the U.S. House of Representatives. But Chisholm had no intention of just sitting quietly and observing, as freshmen congressmen were expected to do. She introduced more than 50 pieces of legislation and brazenly rejected her assignment to the Agriculture Committee, forcing Democratic leaders to appoint her to the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, where she believed she could be of more assistance to her Brooklyn constituents. Chisholm would go on to serve in Congress until 1983, becoming a founding member of both the National Women’s Political Caucus and the National Black Caucus in 1971.

But Chisholm’s most audacious act was yet to come when she threw her hat into the Democratic presidential primary ring in 1972, becoming the first Black candidate from a major party ever to campaign for the top spot. The road wasn’t easy. Chisholm faced backlash from both Black and White male leaders because she was a woman. She was blocked from participating in televised debates, and after taking legal action, was allowed to make only one speech. Undeterred, Chisholm ran on the campaign slogan, “Unbought and Unbossed,” attracting students, women and minorities to the “Chisholm Trail.” Despite meager financial support—she paid for much of her campaign with her own credit card—Chisholm was able to win 152 delegate votes with her gutsy and honest style.

Although George McGovern would become the presidential nominee that year and face Richard Nixon, winning had never been Chisholm’s only goal. Her real objective, in a race where one of the candidates was George Wallace of “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” infamy, was to open the door for other Black and female candidates, and to make sure that minority voices were included in the national conversation.

Chisholm died in 2005, just three years before Barack Obama was sworn in as the first Black President of the United States. She undoubtedly would have been thrilled to see that barrier finally crossed by a Black man, and perhaps even happier to know that our new Vice-President Kamala Harris, a multi-racial woman who is also the child of immigrants, considers herself simply “American.” Because as Chisholm believed, “we must reject not only the stereotypes that others hold of us, but also the stereotypes that we hold of ourselves,” if we are to truly rise.

Background sources for this article include: Unbought and Unbossed, Shirley Chisholm’s autobiography published by Take Root Media, 40th Edition, 2010; The Archives of the U.S. House of Representatives; and The National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian

Other interesting reads about Shirley Chisholm:

CHISHOLM, Shirley Anita, History, Art, & Archives: US House of Representatives

Shirley Chisholm, National Women’s History Museum

‘Unbought And Unbossed’: When a Black Woman Ran for the White House, Smithsonian Magazine

Shirley Chisholm: Facts About Her Trailblazing Career, History

Shirley Chisholm (November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005), National Archives