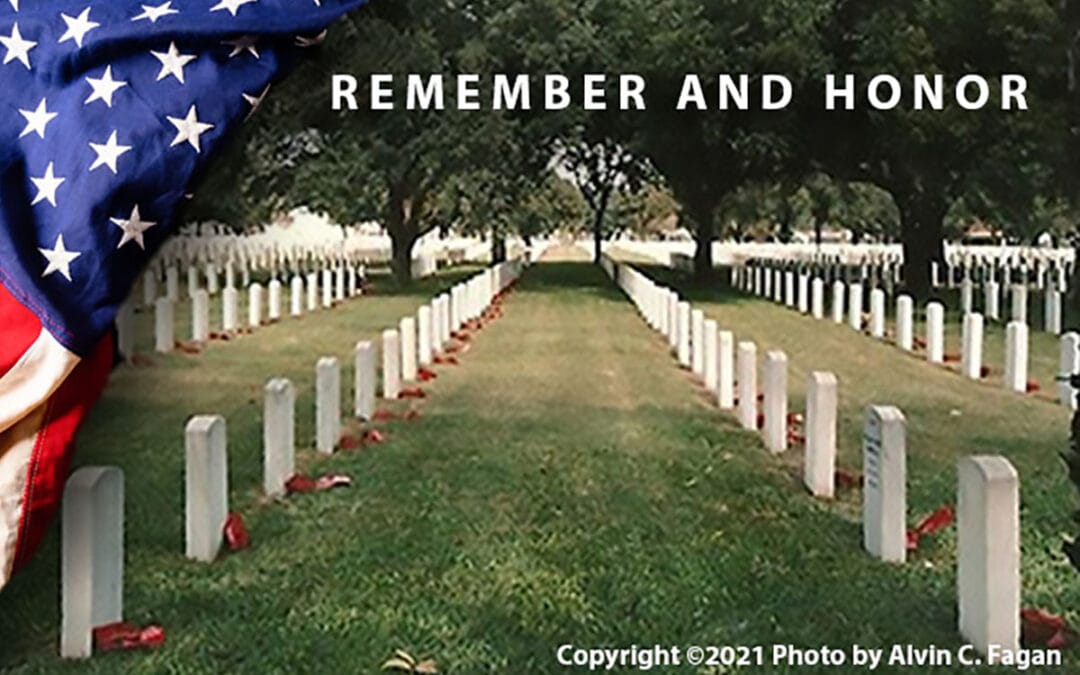

Publisher’s Note on Memorial Day

Publisher’s Note on Memorial Day

Memorial Day was established as a federal holiday to honor those who died while serving in the armed forces. Every year at this time, we at Our Heritage Magazine Online pause to remember the valiant men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice so that we might enjoy the blessings of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And we hold a special place in our hearts for those who fearlessly went into battle and gave their lives while being cruelly denied the rights, dignities, and recognition they deserved as citizens of the United States.

Our Black soldiers have an impressive resume that dates back to our country’s birth. During the American Revolution, approximately 9,000 freemen and slaves fought for the Continental Army. Four African American regiments served in the Spanish-American War, during which they fought valiantly against the British. African Americans, many of them escaped slaves, made up fifteen percent of the naval forces during the War of 1812. During the Civil War, Black leaders such as Frederick Douglas encouraged Black men to become soldiers to ensure their citizenship; by the end of the war, roughly 180,000 Black men served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 10,000 in the Navy. WWI, WWII, the Korean War, Vietnam, the Gulf War—Black soldiers died in all of them.

The resume of enduring service is lacking in one area, however—in the space designated for medals, awards, and recognition for achievement and valor. Black soldiers displayed true strength of character by volunteering their own lives to protect a nation that didn’t consider them as full and equal citizens. Over one million Black men and women served in the armed forces during WWII, but not one deserving Black service member would be honored with one of the 432 Medals of Honor bestowed at the end of that war. It would take 50 more years to correct this injustice. Although Bill Clinton retroactively awarded the Medal of Honor to seven Black servicemen on January 13, 1997, it was too little and far too late—only one of the men was still alive to accept the honor and enjoy the long overdue recognition.

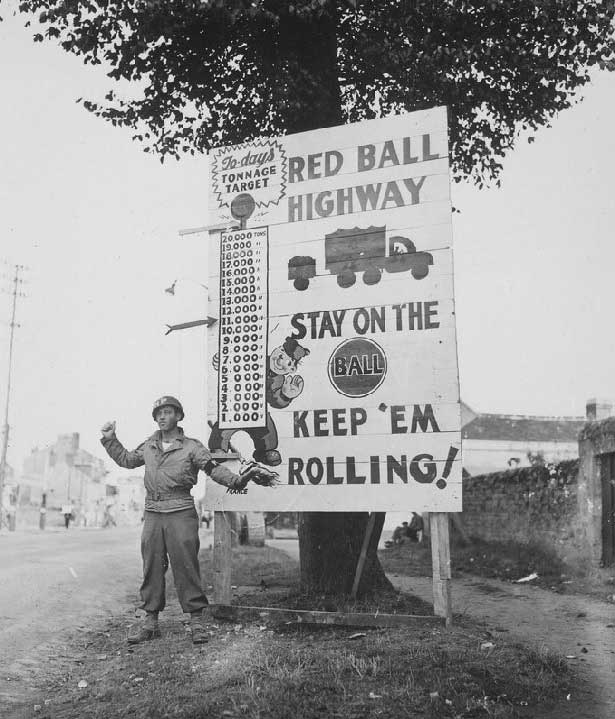

While every soldier that has served our country honorably from its inception holds a special place in hearts and minds, we at Our Heritage Magazine Online will be spotlighting the many unsung Black heroes who gave their all to protect this country while slavery, segregation and racism were a bitter fact of life. Our profile story this month is on the Red Ball Express, a vital WWII transport and supply unit made up of mostly Black men who were fighting a war on two fronts—against fascism abroad and racism at home. Upon forming the Red Ball Express after D-Day, Brigadier General Ewart G. Plank had declared, “Let it never be said that [a lack of supplies] stopped Patton when the Germans couldn’t.” And it didn’t—because of the devotion to duty of thousands of Black men who had been denied their full rights as American citizen, but who were committed to doing their part to win the war. These men, along with so many before and after them, were denied recognition not because they lacked outstanding accomplishments, but because of the color of their skin. At Our Heritage Magazine Online, we are honored to share many of their inspiring stories with you.